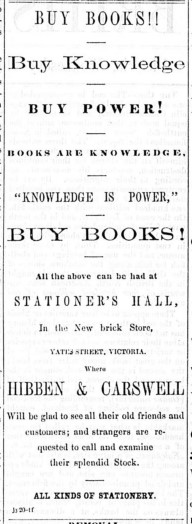

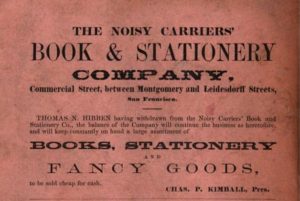

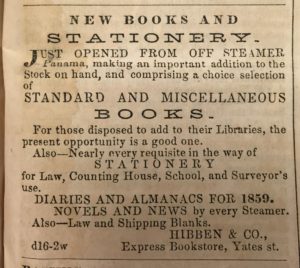

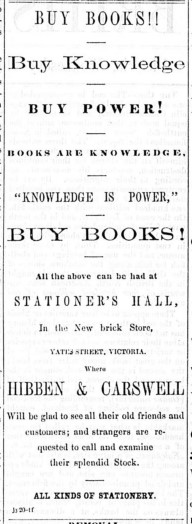

I was recently contacted by someone who is writing a biography of Robert Carswell, founder of the legal-publishing firm Carswell Company in Toronto in the mid-1860s. She wondered, just as I once did, if there was any connection between her subject and my Victoria bookseller James Carswell, a partner in Hibben & Carswell from 1858 to 1866.

Both of us had come across claims, like one here, that after dissolving his partnership with Hibben, James had moved to Toronto to co-found the legal-publishing firm. However, based on newspaper articles from the time and various archival records I’ve collected, I have concluded that this is not true.

In 1867, just a few months after leaving Hibben, James was reported to have opened a general store in Cowichan:

James was still in Cowichan in March 1868, when he made the news for capsizing his canoe in Cowichan Bay:

By 1871, James had quit BC for Glasgow, where his wife, Elizabeth Ferguson (and likely he himself), was from. In a letter published in the Colonist, Reverend Thomas Somerville (a minister from Glasgow who had been with the Presbyterian church in Victoria) reported that James had set up an agency business there.

On October 19, 1872, James died in Glasgow. Although the local BC newspapers reported (with the same Rev. Somerville as the source) that James had “cut his hand severely and bled so freely that he never recovered,” his Scottish death certificate records the cause as epilepsy. It also states that he was 47 years old and a restaurateur at the time of his death.

Although it seems highly unlikely that James could have fit in the co-founding of Carswell Company in Toronto, I thought there might still be a familial connection between the two bookish Carswells. However, finding any evidence of this has also proved elusive.

We know from James’s marriage and death certificates that his parents were John and Anne (Finnie) Carswell, and that he was born in about 1825, whereas Robert was born in Colborne, Ontario, in 1838, to Hugh and Margaret Carswell, both originally from Glasgow.

So they weren’t brothers. But perhaps cousins or uncle/nephew?

Maddeningly, I haven’t been able to find a birth record for James Carswell in Scottish archives. However, John Carswell and Anne Finnie are recorded as having multiple children, including a son named Hugh in February 1825. Huh. James Carswell was 47 in October 1872, so I concluded that his birth year was 1825. Were James and Hugh twins? One and the same person? Or was James’s age perhaps recorded incorrectly at his death?

I still don’t know, but even so, this Hugh Carswell would have been too young to have fathered Robert Carswell in Colborne in 1838. And there the mystery still remains…

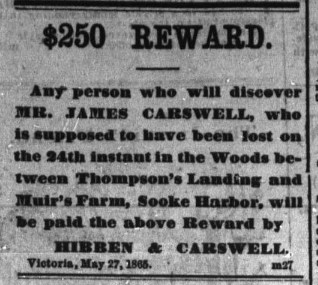

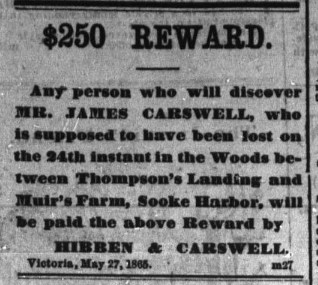

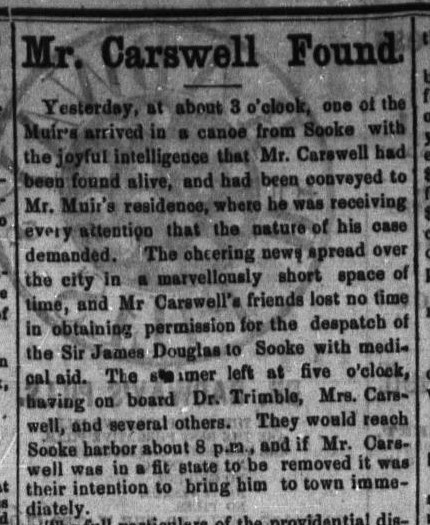

And then, hurrah, came the headline on May 31: “Mr. Carswell Found!” What’s more, he was reportedly in good condition and spirits.

And then, hurrah, came the headline on May 31: “Mr. Carswell Found!” What’s more, he was reportedly in good condition and spirits.