Since starting my research about early BC booksellers, I’ve been curious about why they were so often called stationers.

True, most bookstores of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries sold stationery products in addition to books (as they do today). But it turns out that their proprietors’ common title of “stationer” had a lot more to do with the historical origins of bookselling than with their inventory.

“In the Middle Ages, booksellers in Rome were called stationarii.”

In the Middle Ages, booksellers in Rome were called stationarii, “either from the practice of stationing themselves at booths or stalls in the streets (in contradistinction to the itinerant vendors) or from the other meaning of the Latin term statio, [meaning] entrepôt or depository…The term stationer soon became synonymous with bookseller.” (1)

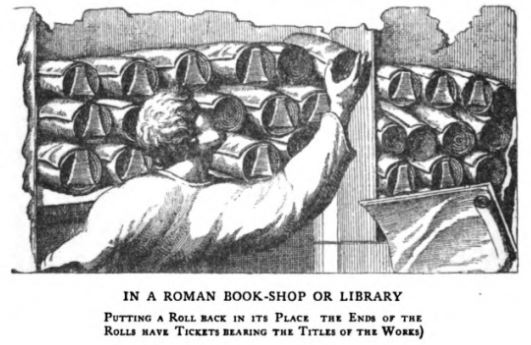

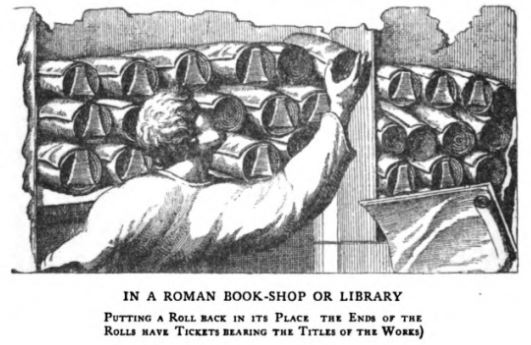

It is easy to romanticize these stationarii at their stalls, disseminating learning and ideas to a literate Roman public. However, the Middle Ages book trade evolved from a less-than-wonderful method of making books that were both plentiful and cheap.

Centuries earlier, in the time of the emperor Augustus (d. AD 14), “every respectable house possessed a library, and among the better classes, the slave-readers (anagnostœ) and the slave-transcribers (librarii) were almost as indispensable as cooks and scullions.” (2)

Initially, “these slaves were employed in making copies of celebrated books for their masters; but gradually the natural division of labour produced a separate class of publishers.”

The first of these was a man named Atticus, who “saw an opening for his energies in the production of copies of favourite authors upon a large scale. He employed a number of slaves to copy from dictation simultaneously, and was thus able to multiply books as quickly as they were demanded.”

By the time of the stationarii in about the thirteenth century, monks and university-trained copyists had largely replaced slaves as the main source of transcription labour. And two centuries later, the printing press would, when it came to book reproduction, displace the human hand for good.

Notes

(1) Henry Curwen, A History of Booksellers, the Old and the New (London: Chatto and Windus, 1873), 13-14.

(2) This and the next two quotes are from Curwen, 10-11.